The romantic’s guide to Vietnamese food

10 dishes that strummed our heartstrings (and 17 honorable mentions)

Piper and I moved in together in 2021. On the first night in our unfurnished apartment, we set up camping chairs on the hardwood and ate takeout Vietnamese. It was how we celebrated in comfort, and how we sought comfort on tough days. Now, this cuisine is a proxy for the only home we’ve yet known together, 1018 Harding St., New Orleans, Louisiana. We’ve followed it back to the source, a pilgrimage years in the making, and with the circle complete, we’re finally ready for guests. So, allow me to dust off the front steps, cue the dinner-party playlist and welcome you to our home away from home: Vietnamese food.

What should you eat when you travel to Vietnam? In short, anything and everything. Ok, not everything. Some things will make you sick, some are hard nos for other reasons, but most of what’s available is safe, hygienic and mouth-watering. Piper has even gone on the record (twice!) calling Vietnamese food “the best in the world”. Subjective, yes, controversial, maybe, but there’s a case to be made. So, before I unleash our top dishes, allow me to take the stand:

Value. 12k VND is a standard banh mi price, as is 20k for a tray of 12 delicate banh beo cakes (VND is 26k to a dollar, you can do the math). Variety / regionality. After 6 weeks of food tours, food blogs, and questioning waiters for 3-5 meals per day we still recognized only about 10% of most menus. Freshness. Each spread is a vibrant polychrome—red, white, green and orange at a minimum. Flavor. Starchy rice (in one form or another), tart lime, fiery pepper nibs, savory grilled meats, and umami-sweet nuoc cham (fish sauce and sweet vinegar— remember that name!). No corner of your palette is left dormant. Textured. You’re likely to encounter 3+ of the following (per bite): spongy, springy, crispy, gooey, crunchy-dry, crunchy-juicy, leafy, soupy, saucy, et cetera, et cetera… Interactive! The finishing steps are often left to the eater, such as adding chilis, lime and herbs, scissor-slicing your pancakes into bite sizes, digging snails from their shells, rolling a roll, or manning your hot pot. Abundant. We once turned out of our Saigon hotel for dinner and the security guard said, “there’s no food that way!”. There were 12 places to eat in the first block. He wasn’t totally wrong, relatively speaking— on a market road it’s more like 60 to a block. Romance. Vietnamese restaurants are the anti candlelight-white-tablecloth experience. Yet mashed into a tiny table with your dining partner, soaking in sweat, sipping beer through a straw— it brings forth a closeness of spirit that tiny votives and single-rose vases can’t quite match.

We spent six weeks in Vietnam and had exactly 2 non-Vietnamese meals. That’s 98% fidelity. Somehow we never craved anything else, truly. Still, with 100+ meals under our belt we tried nowhere near the gamut (see “Variety / Regionality”). Within this unscientific sampling, we’ve picked a few standouts. Some you may find at your local pho joint, others you may have to come straight to the source. Either way, I hope you treat yourself to one or another next chance you get.

Soup

Pho

Iconic. Pho represents Vietnam like pizza does Italy or unsalted baked beans do England. Pho broth is near perfect, and as I’m sure you’ve felt before, slurping it down is like laying a cashmere blanket on your insides. Personalize your bowl using the mound of fresh herbs, bean sprouts, chilis, limes, and sauces served alongside. The makeup of sides varies from north to south, and is debated as a proxy for the country’s cultural divide. You may hear a northerner referring to the “lavish” pho sides in Saigon (read: freewheeling liberals), or a southerner referring to the “delicate” northern style (read: uppity elitists). We didn’t discriminate. Our top order was pho tai, which is served with thinly shaved rare beef. The cattle are here are lithe and gamey, so thinly-sliced is the way to go (slow-braised is good too). If you’re lucky, you may get a side of fried dough sticks to soak up your broth.

Banh canh

The preparations of banh canh vary widely, depending on what word you put next. The unifying element is the noodles— thick, jiggly tapioca strands. The two most memorably banh canhs we had were completely different. Banh canh rua had a rich tomato-base with a filling of fresh crab meat, shrimp, crab-roe meatball, quail egg, and one of the more shocking ingredients of the trip— coagulated pork blood cubes. Banh canh he, on the other hand, had a light seafood broth with white fish filets, fish cake, and a heaping handful of chives blanketing the surface like lily-pads.

Other standout soups (and where to find them)

Bun bo Hue (Hue) - Famous beef-forward soup from the imperial capital of Hue. Spicier broth than pho.1

Lau - Hot pot. We had it with a delicious Thai-style Tom Yum broth and an adventurous slate of sides, including “unlaid egg”.

Rice based dishes

Bahn cuon

The banh cuon I came to love in Hanoi was prepared unlike anything I’d seen before. There is a large pot of simmering water with some sort of cooktop stretched over like a drum head. It’s splashed with watery rice batter then spread with a squeegee, quickly forming springy rice tortillas. The filling varies, but is often ground pork and wood-ear mushrooms. It’s finished with a topping of fried shallots and served with the familiar sides and dips.

We ordered banh cuon at two subsequent stops down the coast, and were each time served something wildly different. Too different to be explained by regional preference— we must have been reading it wrong. To a non-speaker, the Vietnamese language seems to use 3-5 letter words exclusively. It even feels like the same 20-30 words. It’s very confusing. Look a little closer and you’ll notice dashes and squiggles decorating letters like toupees and mustaches, and a new confusion will dawn: how many sounds can a single letter possibly make? I can’t answer that question for you, but it explains why we were sometimes served unexpected things.

Bun dau

Bun (round rice noodles) may be the safest of all Vietnamese ingredients. Dau is deep fried silken tofu, another mild flavor and easy texture. Together bun dau makes for a comforting dish. It’s served as a large platter of compressed bun chunks, dau cubes and a massive pile of fresh herbs. The traditional dipping sauce is a fermented shrimp paste, inexplicably bright purple, which you’re encouraged to mash with pepper coins, to taste. Nuoc cham, soy sauce, and chili paste are also available.

The two namesake ingredients carry the dish. Silken tofu is so elegant. It’s smooth and creamy like an umami flan. The noodle hunks are dense, a perfect counterpoint of texture. Each one dutifully sponges up your sauce of choice and whispers a flavor of its own. Wrap it all in a big fat basil leaf for the full experience. Or keep it simple, stick to the bun & dau, and relish in the comfort of these mild-mannered staples.

Banh beo

I cherish the moments that Piper looks into my eyes with the tenderness she looks at a platter of fresh banh beo. That’s the intensity of her love affair with these strange little saucers. I get it, there’s a lot to love.

The cooking method is pretty ingenious, a towering lattice of bowls is filled by a teapot of batter then steamed. They come out in batches of 2 dozen or so. When fresh, they’re warm and gummy, when cooled they’re springy and still delicious. Each starchy disc is a canvas for the chef to decorate in their own way. We tried beos starring pumpkin stew, pork broth, fried baby shrimp, chives, and more. I don’t ever recall having the same toppings twice.

Yes, it’s delicious, and yes, it’s got range, but the real fun is eating it. The ritual of banh beo is sincerely satisfying. First, scrape two straight lines along the dish with a metal spoon, creating 4 equal quadrants. Set down your spoon. Next, apply nuoc cham, chili oil, herbs, and any additional sauces, to taste. Your beo dish should be sloshing. For balance, dust in crushed peanuts until the sauce is a pasty texture. Retrieve your metal spoon. One by one, unearth your beo quadrants. Eat them. Slurp up the remaining sauce. Finally, stack your empty dish onto the others.

Adding to your neat boneyard of porcelain dishes is the final, joyful touch. There’s an animal pride to it, like hermit crab collecting shells. Your stack is your own, a public measure of vitality in the arena of Vietnamese eating.

Other standout rice-based dishes

Pho cuon (Hanoi) - Specialty of Truc Bach island in Hanoi (❤️). Uncut sheets of pho noodle rolled with protein, stacked into a pyramid, then eaten with nuoc cham.

Pho chien phong (Hanoi) - Another specialty of Truc Bach (❤️ ❤️ ❤️). This time pho noddle sheets are stacked and cut into cubes, then deep fried and topped with veggies, meat and some sort of gravy. You don’t think you’ll be able to finish it when it’s served. Spoiler, you do.2

Bun thit nuong - This is the closest we got the classic “vermicelli bowl” that’s so common in American Vietnamese restaurants. There’s a surprise at the bottom of your noodles, grilled pork and egg rolls - julienned veggies! A go-to when it was available.3

Banh trang nuong (Da Lat) - Vietnamese pizza. Other than being round, it has nothing in common with pizza. The “dough” is a single circular rice paper, covered in any variety of local ingredients and grilled. We had one version of this that was borderline inedible, and another that was so good my eyes started to water.

Com tam (Saigon) - “Broken rice”. These are the rice kernels that are unsuitable for sale. Instead, they’re made into cheap meals, usually topped with sautéed morning glory and grilled pork, with a side of (do I even have to mention it anymore) nuoc cham.4

Banh can (Nha Trang) - Rice batter cooked in tiny clay pots over coals. Often topped with meat, seafood, or quail eggs. Dunk them in a nuoc cham / green mango / chili pepper sauce. Delightfully spongy and crispy, even post-dunkage.5

Banh xeo - Greasy crepes cooked in cast iron skillets on an open flame, filled with anything or nothing. Served with herbs, sauces, and dry rice paper. Slice with scissors, roll up with your choice of ingredients, and allow the hot Xeo to cook the rice paper. Dunk in (you guessed it) nuoc cham.6

Meat / Seafood

Ech Chien

We have a fellow Tulane alum to thank for pointing us towards this dish (with her own heartfelt take on Vietnam). It translates to “fried frog”, and surprise, that’s exactly what it is. Our lone experience with ech chien was enhanced by the buzzing Saigon nightlife around us. It was a Friday evening along the canal, and dozens of groups were seated across from the dark, shimmering water, smiling and enjoying a weeks-end meal. The crispy frog legs were coated tastefully in nuoc cham and ginger, with just enough spice to make our beers real appetizing. Eating this dish, I realized that I’ve overlooked frog meat, and how it’s basically a delicious, juicy hybrid of white fish and chicken. In this country, nothing edible is overlooked, so I wasn’t surprised to see it carrying the same flavors and tempting presentation as the rest of the cuisine.

Other standout meat / seafood dishes

Bun cha (Hanoi) - Pork meat pinched between two grill grates and cooked over coals (an ingenious method, I’m stealing it). Served with bun, herbs, and a fat bowl of nuoc cham intended as the base of a delish, DIY soup.7

Nem nuong (Hue) - Pork sausage skewered onto lemongrass stalks and grilled. Sound good? Yeah, it’s good. Served with a familiar plate of sides and dry rice paper for a roll-your-own experience. The sausage softens the rice paper, and by the time you’re biting, all the textures have aligned.8

Oc (Coastal) - Snails! I’m always blown away by how palatable snails are, despite their reputation. These were chewy, but not overly so, and paired with all sorts of dipping sauces. Known as a drinking snack, they’re served with a bucket of beer (pay for what you drink).9

Com hen (Hue) - A tremendously complex dish flavor-wise. It’s got a ton of ingredients— sliced fig, green mango, banana flower, fried pork skin, peanuts, herbs, etc… The star is the hen, which are tiny river clams no bigger than a ball bearing, piled on by the hundred.10

Banh mi

I’m guessing you already know and love the Banh Mi. It’s got to be Vietnam’s second most famous culinary export (even though its key ingredient is from France). Banh mi stands are set up like Subways, with a glass case showcasing all your options. Unlike Subway, each stand has wildly different options. Usually we’d be paralyzed by overwhelm and ask for dealers choice. Or we’d go with op la, which is the whimsical word for “egg”. These stands were among the few places that didn’t adhere to strict mealtimes, and we leaned on them heavily in our ad-hoc dining schedule.

Drinks

Nuoc mia

Nuoc mia (aka sugarcane juice) was the lifeblood of our motorbiking trip. The motorbikes needed petrol, and we needed nuoc mia. I’m exaggerating slightly, we didn’t actually try it until a week or so into riding. Our hesitation was based on a false notion that it’d just be sugar water— a stomach ache waiting to happen. In reality, it’s no sweeter than fruit juice, and the crushed cane adds a counterbalancing earthiness. The juice is cloudy and substantial, maybe from the fiber of the stalk. There’s a hint of citrus from the kumquat that’s impaled on a stalk before crushing it.

The ease of running a stand may account for their popularity. Each one has a small engine which turns two inversely-rotating rollers. Sugarcane stalks are fed through in small bunches, and the juice is funneled directly into a waiting cup of ice. It only takes a few seconds. The success of a stand can be measured by the mound of discarded husks that collect alongside.

But ease alone can’t explain a nationwide obsession. For a hot, humid climate, nuoc mia hits all the right notes. It’s watery enough to drink in long, luxurious gulps. It doesn’t make you pucker or overwhelm with any other flavors. It’s credited with medicinal qualities and pitched as replacement for coffee, difficult things to prove but easy to entertain after having a glass. During our sweltering slalom on the Vietnamese roadways, nuoc mia and its refreshing boost is solely accountable for rescuing a few of our most despairing moments. This time, I’m not exaggerating.

Vietnamese coffee

Coffee is a way of life in Vietnam. Cafes crowd every city block and every country crossroad. They are cornerstones of social life.

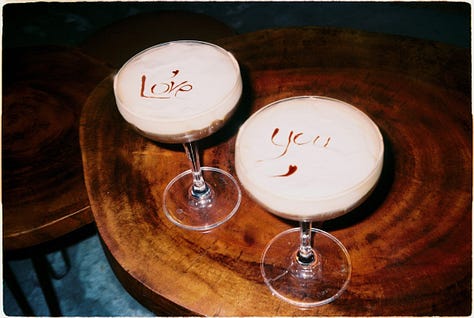

Vietnamese coffee is made from Robusta beans, not Arabica like in most of the world. Ounce per ounce, your coffee will have 4x the caffeine you’re used to (🤪). Some popular preparations are sua (condensed milk), dua (coconut cream), trung (whipped egg), and muoi (salt cream). We’d usually go for ca phe den da (black coffee on ice) in the morning, then one of the decadent options for an afternoon pick-me-up.

On our first day in Vietnam, we stumbled into a Hanoi cafe to stave off the jet lag. We ordered and were gestured to sit (it’s usually table service), so we ventured through the cafe. It went up four stories, each one with a cozy nook, and the top floor with a sweeping view of the neighborhood (albeit limited by smog). This was the first time it really sunk in. We were in northern Veitnam, and would be following our wildest dreams for the next 4.5 months. Soon the caffeine was pulsing through my veins, along with excitement and anxiety about the mysteries this era had in store. It was joined by a welling adoration for my wife sitting across from me, and finally pride, that we had managed to wring this vacation free from the jaws of conventional American living. Maybe it was the caffeine talking, but in hindsight, damn was I glad our 6 weeks in Vietnam would be super-powered by Robusta.

Other standout drinks

Tra tac - Kumquat tea! Served anywhere the sun shines, it’s a lighter alternative to nuoc mia and a great pick-me-up. I imagine it would’ve mixed swimmingly with some tequila…

Bia - Beer is commonly served room temperature with a glass of ice and a straw. Even if the can is cold, you’ll still be given ice. We quickly got accustomed to drinking watered down lagers (they were pretty watery to begin with), and given the heat, there were actually some merits. It’s not something we’ll be bringing home with us, although beer through a straw was fun.11

Desserts

Tet cake

Sticky rice has been my favorite food since childhood, when my Thai nanny Pao made sticky rice cake for every birthday. It’s not easy to find back home, and as much as I hate to say it, mango sticky rice bores me! My prospects have improved drastically here in Asia.

On our first day of motorbiking we found ourselves stranded at an open air bodega while our flat tire was fixed. I was drawn to a stack of mysterious, saran-wrapped neon green lumps. They were sticky rice bars— sweet, starchy, chewy, dense and stuffed with earthy mung bean paste. I couldn’t believe my luck, and we bought an extra 4 for the road.

Fast forward to our final night in Vietnam, when I was pining for this dish one last time. I’d read about a shop selling Tet cake, a sweet and savory sticky rice treat served during the lunar new year, and we followed Google maps down a dark alley to the address. It was closed. Really, there didn’t seem to be anything there at all, just another concrete home crammed into a long row under dim streetlights. My heart sank, but we heeded our travelers intuition and lingered for a minute. Sure enough, a light flipped on and a Vietnamese grandma in her nightgown ran out to greet us. We showed her a picture of the Tet cake and she nodded vigorously, then yelled upstairs. A younger woman appeared and welcomed us in English. She beckoned us into their small patio, and set up four tiny chairs between motorbikes and sleeping dogs. We were presented a plate with a single Tet cake upon it— a solid brick of glutinous rice stuffed with mung bean and pork. It was never our intention to dine in, but how could we resist. As we ate we communicated in awkward fragments, the subject changing often, but good will overflowing between us. The younger woman was disheveled, clearly having been roused from sleep to translate for her mother, but she was endlessly patient and kind. They couldn’t believe we were here, at their back-alley home, asking for their Tet cake. We couldn’t really believe it either. As we geared up to leave, they channeled their disbelieve into generosity, gifting us an additional 6 Tet cakes. The bag must’ve weighed 8 pounds.

Sticky rice may well have been my first experience of cultural crossover. All these years later, it’s still leading me towards the finer facets of curious living.

Other standout desserts

Tau hu nuoc - We encountered this dish twice and jumped at it both times. There’s a massive (30 inch diameter) pot with a jiggling basin of silken tofu inside. The tofu is sliced off with a shallow spoon, leaving moon-like craters in the pot. It’s combined in a cup with ginger simple-syrup, tapioca balls, and rice-cream. It’s sweet, earthy, warm, and a welcome expansion of my dessert horizons.12

Che Thai - A ubiquitous dish. It’s based off a popular Thai dessert which is known as “sweet soup”. Che Thai stands are mediums for creativity. Behind the counter are rows of preserves and jarred mysteries as if you’re visiting a medieval witch doctor. Strange ingredients like fermented sticky rice are paired with more conventional ones— lychee, tapioca, berries. All of it is mashed into a cup of ice to form a texturally confusing, but undeniably refreshing and sweet-tooth appeasing treat.13

Of all the entry points to a foreign culture, sitting down at a restaurant is the easiest, and the most instantly gratifying. It should be no surprise that wherever we go, our first priority is wedging ourselves into the food scene. Eating in Vietnam came with an element of intimacy. The restaurants are often extensions of the home. We’d find ourselves squeezed into a play-set table and chairs while the children of the house did their homework at the next table, or beside a toddler ogling at our strange faces. Even in the beer halls and sprawling street food villages, the intimate nature was no less present. These were places we felt comfortable, even as total outsiders. We were encouraged to live like a local and stay as long as we wanted.

We’ve come a long way from the camping chairs on Harding Street, but those memories were never far off. The thread of taste and place is firmly anchored, and it’s growing new strands. So yeah, after 13 years of Vietnamese food in New Orleans and then 6 weeks of total submersion, there’s a lot of emotion attached to these flavors. I guess I can acknowledge it—we aren’t objective critics! Nonetheless, the superlatives are true to us, through and through. My hope is that you read this, and if you aren’t converted already, you sit down with an open mind next time you get Vietnamese. With a good order and some luck, maybe you’ll start feeling some of what we feel.

P.s. I would be remiss not to mention Luke Digweed and Tom Divers, contributors on our favorite Vietnam resource, Vietnam Coracle (Tom is the site’s founder). These articles in particular guided us to some of our favorite bites:

Bonus photos!

Banh Can in Da Lat

Banh Xeo in a few forms

Oc in Saigon

Awaiting my Che Thai order with no clue what I was getting / Che Thai in Hoi An

I cannot wait for you to come home and cook for us!!

Also the photos... this might be your most important post yet.